This post was originally published on Autocar

It took a brave soul to go into a desert in a 1920s car. No satellite phones, either

Did people try to drive through the wilderness before 4×4 cars were invented?

Well, of course they did, such is the human spirit. As far back as the early 1900s, even – but the story that captured my imagination came from 1927.

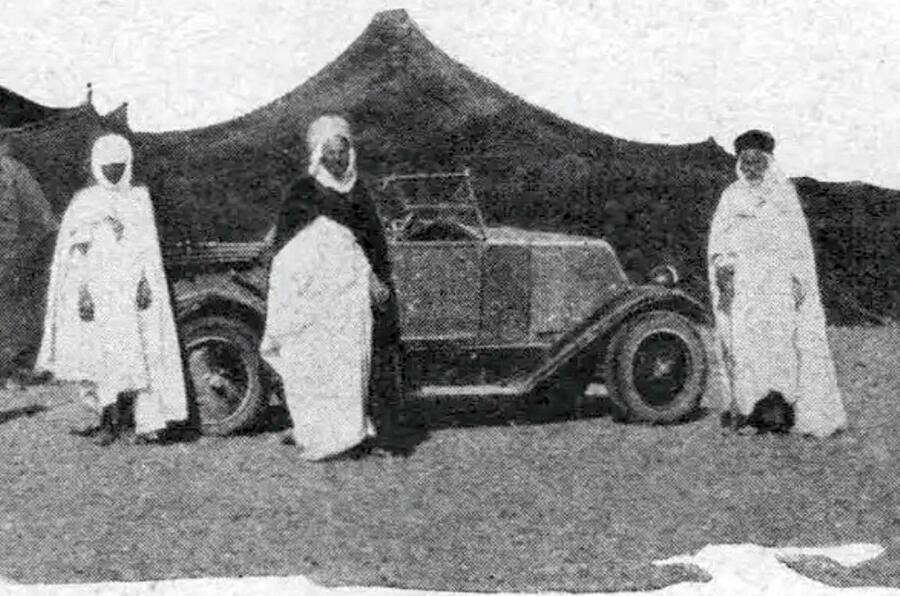

Imagine yourself as a British woman a century ago. Would you fancy driving a small, 15bhp Renault convertible across a large part of the Sahara desert inhabited by armed nomad groups, having no mechanical knowledge and no experience of driving on sand, with your two young children in tow?

Obviously not – but you’re not Winston Churchill’s trouble-making, globetrotting, Soviet-seducing, writer and artist cousin.

Clare Sheridan reported in The Autocar: “I do not happen to be a motor tourist of the conventional kind, I dislike my species and love to get away from the tourist routes.

The discomforts and the dangers of ‘the track’ rather add to my zest in motor adventuring. Indeed, for a person who is not likely to be able to afford a new car, I am rashly imprudent.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

“The garages in Biskra smiled pityingly at me when I announced my intention of setting out [for Ourgla, 235 miles south].

Having realised, however, that I could not be dissuaded, they advised me to take every conceivable spare part, as well as four inner tubes, two tyres and a second spare wheel. Now this I could not afford to do. However, I consented to take two inner tubes, a shovel and a [local] mechanic.”

She was on a recognised road for only about 10 miles before heading into the desert. “The earth’s surface was composed of hard, chalky, rocky ridges, which, even at [barely 10mph] shook us horribly. Our coachwork after a while began to squeak and rattle and groan.”

And as soon as she had passed this hard territory, Sheridan got the car hopelessly stuck in a sand dune. Its wheels spun lamely, a burning smell filled the air and a tyre burst. A jack, floorboards, petrol cans and collected scrub plants all failed to give traction.

Luckily, a caravan of camels passed nearby and the nomads came to Sheridan’s aid. It took 17 men about an hour to free the car.

As the temperature plummeted, another tyre gave up – and so did the jack. As the mechanic fretted in feeble moonlight, Sheridan mused: “The Sahara at night is so lonely, so still, so vast, so unfriendly; one feels that one has no right to be there.” Thankfully, he could fix the issues, and she just about got the car to crest the many dunes thereafter.

“I learnt a lot that night about sand: that you must not hesitate and must not be slow but look ahead and get into second in plenty of time and accelerate full.”

At Touggourt, Sheridan was introduced to a local kaid (‘commander’), who explained that his sports Peugeot had the benefits of an engine encased in a metal lid to keep out the sand and smaller wheels with ‘balloon tyres’ for better grip on it.

From here she proceeded the 60 miles to the kaid’s house at Hadjira and, following a night’s generous hospitality, another 120 miles to Ourgla.

“The track was so wide that it hardly mattered where one drove so long as one continued in the right direction. At one moment I took both my hands off the wheel, waved them wildly in the air, and accelerated as hard as I could. It was so childish, and such fun.”

After a night at Ourgla, Sheridan’s return to Touggourt was hampered by “detestable” headwinds – and her return to Biskra complicated by advice from her friend the kaid to not travel the way she had come but a “slightly longer but infinitely better” French military piste, marked out by iron posts.

“It was one of the most exciting and anxious bits of driving I have ever experienced. Success depended on speed, and if one hesitated, one was lost.

“After 20 miles or more of this agony, we found ourselves on an excellent track, but at midday we stopped, not so much to eat as to do something to the [leather cone] clutch, which was slipping badly. The rest of the journey I look back upon as a most ghastly nightmare of monotony.”

It transpired the military required drivers to register and have their cars examined before using this piste, then go with a guide. “Had we broken down, we would have been left to perish,” reflected Sheridan, “for we had no reserve of food or water and no one expected us.”

It’s a fine line between bravery and madness, so they say…