This post was originally published on Autocar

Mini is one of the most beloved of all the cars ever built, and survived until 2000

We dive into the Autocar Archive to trace Britain’s automotive story right from the very beginning

One of the most widely consequential inventions of all time – the self-propelled carriage – emerged in the mid-1880s from Germany, courtesy of Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler, and it was a business deal with the latter that sparked the British automotive industry into existence at an old cotton mill in Coventry.

As the 20th century dawned, cars grew steadily in popularity among the monied few – until the 1920s, when truly affordable models started to emerge thanks in no small part to the rapid and vast industrial expansion that the First World War had necessitated.

For the masses

Across the pond American firm Ford was forcing down the cost of its Model T using its novel production methods, and so too was this the case at its factory in Manchester.

Meanwhile, alongside a cottage industry scattered around the land were the busy factories of Coventry, producing several thousand cars annually at each. Fittingly, the first car The Autocar fully evaluated was an affordable Rover, the 8hp saloon.

Some 18,000 of these would be made in just five years, thanks in large part to continual price reductions, as seen with the Model T. It was £230 at the time of our 1920 article – £8640 in modern money, or about 10% more than the average annual wage for a male factory worker.

“Judging from the performance of the car on the road, the interior workmanship of the running gear has not in any way been allowed to approach an inferior quality with a view to cheapness of manufacture,” we reported.

The fact that we weren’t too bothered about the cruising speed being just 28mph, the two-cylinder engine giving “a slight thump with each explosion” and the suspension having “a slight tendency when traversing exceptionally bad spots for the back of the car to give little sideway kicks” only goes to show that automotive engineering, while by that point mainstream, was still very much in its infancy.

What better demonstration of the democratisation of personal transport than the fact that, just eight years later, the similarly conceived Austin 7 that we tested was not only a far better car but also only £170 – despite being a fancier fabric-roofed saloon variant.

“The little machine is very comfortable in all ordinary circumstances,” we said. “Below 20mph the engine is rough and noisy; above that speed it becomes smoother, and the faster the engine goes the quieter it becomes.

“The turning circle is not small, but the fact that the car is so easy to handle makes this of very little performance.” Production would end two years later with almost 300,000 cars having been made, with Birmingham’s Austin and its Oxford rival Morris contributing more than half of the British total.

Promising consolidation

Following the end of the Second World War, it seemed clear that consolidation was the future for major industry, as the complexity of the products increased and large economies of scale yielded profitability. Thus the bulk of the industry was grouped into the three large groups.

The British Motor Corporation’s Austin/Morris Mini needs no introduction now, but back in 1959 it was an immensely exciting novelty – and the convention-breaking, £537 compact saloon lived up to all of its fantastical promises in our estimation.

“[BMC is] to be congratulated on producing, at a truly competitive price, an outstanding car providing unusual body space for its size, and one in which persons can enjoy comfortable, safe and economical motoring,” we enthused.

Of course, the Mini became emblematic of British culture, with more than five million examples being produced over the next four decades – although actually it was outsold at home by its now-forgotten big brother, usually known as the Austin/Morris 1100.

“The staff of this journal have never been so unanimously enthusiastic about the overall qualities of a car; the few criticisms are minor in character. It is obvious that a far-sighted and thorough engineering job has been done,” we said in 1962. “It is fully capable of challenging all the currently popular European small cars.”

With such engineering nous and products, what could possibly go wrong?

Essex excellence

Ford had been manufacturing cars in the UK for so long and was so prominent in terms of both popular culture and the national economy that, by this point, many considered it to be a British brand – and quite right too, when Dagenham’s bespoke output would appear as aliens back at Ford’s home in Detroit.

And these cars were just as good as their pure-blooded British rivals from the Midlands, as shown by our comments at the 1962 arrival of the future top-selling Cortina. “Technically this model offers nothing fundamentally new, yet the components have been endowed with a degree of refinement that makes it exceptional. For a family man who wants both space and economy, it will obviously have a strong appeal.”

Equally consequential was the Fiesta – almost always the supermini par excellence from its introduction right up until the closure of Dagenham in 2002.

“Is it worth waiting for?” we asked in 1976. “Yes. It brings a touch of flair, driver enjoyment and all-round efficiency to the small car market. One can expect Ford to have looked very hard at their rivals and to have gone into everything very carefully. These expectations are certainly confirmed, and the product fulfils one’s high hopes.”

Premium Allure

The British industry had been about luxury cars for longer than it had been producing affordable metal, and our nation’s engineers never forgot how to excel at the rarefied end of the spectrum. As BMC and Ford prospered, an addition to the utmost luxury offered by Bentley and Rolls-Royce came in the form of what we now call ‘premium’– best shown by two firms now unified as Britain’s only native volume car makers.

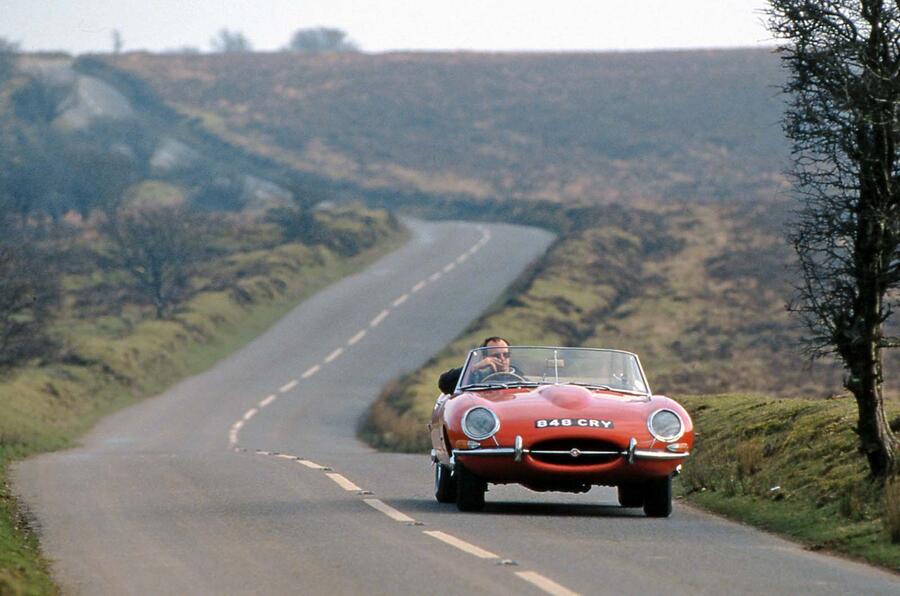

Jaguar’s real breakthrough came with the E-Type of 1961 – as beautiful and as exhilarating to drive as a Ferrari yet one-third of the price. No wonder even Enzo was envious.

We gushed: “It’s a major advance, amounting to a breakthrough in design of high-performance vehicles for sale to the public. This grand touring coupé is vastly superior to its predecessors in a number of respects and to competitors. It offers what drivers have so long asked for, namely sports racing car performance and handling combined with the docility, gentle suspension and appointments of a town car.”

Nine years later came the Range Rover, combining the capability of the rugged, simple-as-could-be Land Rover off-road 4x4s with agreeable road manners, a big V8 engine and a luxurious interior.

We summarised: “Most impressive ride, on or off the road. Cornering very good, but excess roll. Superb driving position and high standard of comfort. Very good performance.”

And concluded: “We have been tremendously impressed by the Range Rover and feel it is even more deserving of resounding success than the Land Rover.”

Pinnacle of performance

Britain has always been one of the foremost forces in international motorsport, and in turn it became the leading provider of niche sports cars and supercars.

And as clever engineering brought about a British domination of Formula 1 and other forms of top-end motorsport throughout the 1960s and beyond, this position was strengthened immensely. Today, eight of the 10 Formula 1 teams are based in Britain; and for decades, ‘specialist cars’ have been what this nation’s industry has done best.

In the early 2010s there was famously a trifecta of watermark-raising hypercars, respectively from Maranello, Stuttgart and Woking – and the last of those didn’t look even slightly out of place, despite McLaren Automotive having existed for a scant few years.

“This is a car whose maker has taken joy in its engineering and greater joy in presenting it to the driver,” we concluded of the 903bhp, £867k, plug-in hybrid P1. “If we had 100 cars, there would be many days when only a P1 would do. You can’t ask for more than that.”

And Britain’s vanguard stalwarts deserve no less admiration, as our 2018 verdict of the Aston Martin DBS Superleggera demonstrates: “This is a big, powerful, elegant, front-engined, 12-cylinder, blood-and-thunder GT alike in concept to so many we’ve known and loved from Aston Martin.

“But it’s also such a stunning one to behold, and so stellar to drive in its singularly enriching and enticing, occasion-cherishing, long-distance mould, that it sets a new standard for its maker.”

Foreign friends

As it would be remiss to not mention Essex Fords when discussing the finest British cars, so too would it be to ignore the products today turned out by our countrymen bearing Japanese badges.

Since the 1980s and 1990s respectively, following the demise of the nation’s dire British Leyland conglomerate, Nissan and Toyota have been providing Britain with reliable, affordable machinery – and in the case of the former, changing the world a few times.

When the Qashqai arrived in 2007, we said: “This is a capable, likeable and interesting hatchback with excellent levels of refinement that offers a refreshingly different approach to family transport.”

And boy, did the public agree, not just here but everywhere: this Cranfield-designed, Sunderland-built car is the reason why almost every mainstream model today is taller than traditionalists consider proper.

Five years later, it was followed by the first mass-produced electric car: “The Leaf won’t suit everyone, but it is easy to see its huge potential as a comfortable and practical school-run car or short-distance business commuter. It finally proves that the everyday electric car isn’t just wishful eco-thinking, even if the price for private buyers is still too big an ask.”

Looking ahead

The future of automotive has rarely if ever looked so uncertain, but we can take heart from the fact that for every embarrassment in the history of the British automotive industry – and there have been many – there is also an example of innovation and excellence.