This post was originally published on Autocar

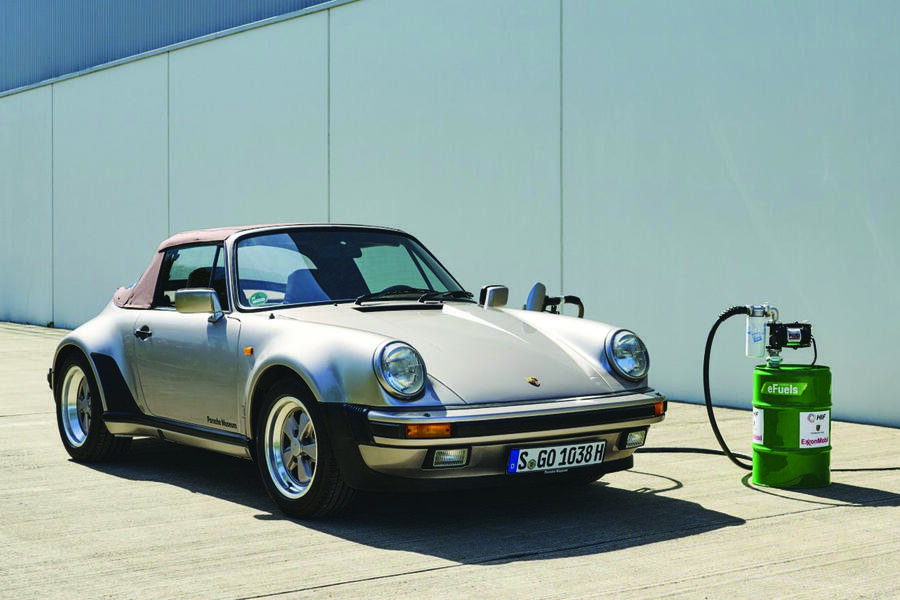

Porsche is one of the leading car brands when it comes to exploring e-fuels

‘Carbon-neutral’ synthetic fuels could complement electrification – but they face significant challenges

The impending ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars has raised questions about whether alternative fuel solutions also have a role to play in reducing transport emissions alongside electrification.

Some car manufacturers and governments are working to produce alternative means of fueling a car.

This includes hydrogen-powered vehicles, but other firms are pushing two main forms of fuel: e-fuels and biofuels, both types of synthetic fuel.

So what exactly are e-fuels and biofuels, how are they made and could they enter mainstream production?

We’ve collated all we know about these alternative fuels and put together a comprehensive guide about this technology, so read on for more.

What are e-fuels?

The name ‘e-fuel’ is short for ‘electrofuel’.

E-fuels are a type of synthetic fuel that can be used in internal combustion engines in the same way as normal petrol or diesel.

They’re produced using ‘green’ hydrogen and carbon, often sourced from waste biomass or CO2 captured from the atmosphere.

How are e-fuels produced?

E-fuels are made by separating hydrogen and oxygen from water using electricity. The next step in the process involves capturing CO2 from the air and then combining that with hydrogen using chemical synthesis.

E-fuels are carbon-neutral, because they use the same amount of CO2 emissions as they emit. For this reason, they’re considered by some car brands, such as Porsche, as a potential alternative to electric cars.

An e-fuel’s removal of atmospheric CO2, either through photosynthesis when growing the biomass or by carbon capture, is argued to offset the emissions produced when the fuel is burnt in an engine.

Are e-fuels clean?

Whether e-fuels are as environmentally friendly as they seem continues to divide opinion.

Despite arguably being cleaner to produce, e-fuels still emit gases that are harmful to the environment, similar to petrol and diesel.

According to the non-profit organisation Transport & Environment (T&E), recent testing of e-fuels has shown that synthetic fuel emits a similar volume of NOx gases as a car running on regular E10 petrol while also producing far more ammonia and CO.

There’s also the argument that e-fuels aren’t all that efficient in use. According to Enerdata, vehicles using e-fuels have an energy efficiency measuring 4-5 times lower than battery electric cars.

Pros of e-fuels

There are a few positives to e-fuels.

Some argue that e-fuels are a cleaner source of energy compared with petrol and diesel, due to the methods that can be used to produce them. Electricity required to produce e-fuels can be generated using solar and wind power.

E-fuels are capable of powering modern cars without the need for modifications. They can also be used in heavy goods vehicles and vans.

While other fuels like hydrogen and electricity require new infrastructure, e-fuels can be used with existing fuel lorries, refineries and pipelines, and filling stations can remain the same.

Need to fill up a car using e-fuels? You’re in luck: it takes just a few minutes, like filling up with petrol or diesel.

Cons of e-fuels

The key problem with e-fuels is that they’re costly to produce and can’t yet be produced in large quantities.

They’re also incredibly energy-intensive to produce. In the case of e-fuels, there is a huge energy requirement to overcome to produce the necessary hydrogen.

T&E suggests the EU would be required to produce one and a half times its current energy production to generate enough electricity to power its entire road fleet using e-fuels.

In addition, research from the International Council on Clean Transport (ICCT) suggests that around 48% of renewable electricity will be lost during the process of converting e-fuels into liquid.

For comparison, it was found that when using renewable electricity, a battery electric car could travel up to six times farther than a car using e-fuel.

Despite being cleaner to produce, e-fuels also still emit gases that are harmful to the environment, similar to petrol and diesel.

As with fossil fuels, burning them produces poisonous NOx gases and CO, which pose a health risk for local communities.

Which manufacturers are investing in e-fuels?

Porsche is the front-running car maker in e-fuel development. It invested £62 million into pilot production of synthetic fuels in Chile late in 2022, with a target of roughly 28,500 gallons (130,000 litres) annually.

“The potential of e-fuels is huge,” said Porsche research and development executive Michael Steiner. “There are currently more than 1.3 billion vehicles with combustion engines worldwide. Many of these will be on the roads for decades to come, and e-fuels offer the owners of existing cars a nearly carbon-neutral alternative.”

Despite Porsche heavily investing in battery electric vehicles, CEO Oliver Blume has said synthetic fuels could extend the life of the purely combustion-engined 911 until the end of the decade.

Several other car makers, particularly those with low-volume production outputs, are also keen on using e-fuels to retain combustion engines beyond the end of the decade.

Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna has suggested that “ICE still has a lot to do” and Ineos Automotive CEO Lynn Calder was categoric in predicting “that the combustion engine will continue”.

Mazda has also expressed interest, with the brand’s deputy general manager of R&D Christian Schultze saying describing e-fuels as “an important addition to electrification, as they are easy to implement and they can give an immense effect to the decarbonisation simply by the high number of cars used.”

Renault-owned sports car maker Alpine is also keen on e-fuels.

However, other car makers, such as Bentley and Volvo, are opposed.

What does the future look like for e-fuels?

The UK government has yet to factor e-fuels into its emissions-reduction strategy officially.

A report by the Transport Select Committee recently accused the government of “putting all its eggs in one basket” by effectively mandating a widespread transition to battery electric vehicles from 2035.

The report cited shortcomings in EV charging infrastructure and a shortage of raw materials, which may slow or prevent a smooth transition to EVs.

“As the cliff edge of 2030 (2035, 2040 and 2050) approaches and minds are concentrated, reality will bite,” it said.

The committee urged a “reality check” on the government’s transport strategy and said: “Addressing the existing [petrol and diesel] fleet will be decisive in achieving the UK’s climate goals.”

According to a 2019 report by the International Energy Agency, producing all of today’s industrial hydrogen output from electricity would create an electricity demand of 3600TWh.

This is almost 1000TWh more than the EU’s entire energy production last year, of which just 39.4% came from renewables. And that just to match today’s hydrogen output, not the surplus needed for the mass industrialisation of e-fuels; using electricity that could less wastefully power battery electric cars.

Yoann Gimbert, e-mobility analyst for environmental lobby group Transport & Environment, said in October 2022 that using e-fuels in cars and commercial vehicles risks “[sucking] up renewable electricity needed for the rest of the economy”.

Gimbert added that e-fuels should be diverted to planes and ships, which can’t yet use batteries to decarbonise.

Nonetheless, momentum continues to build globally. Porsche’s e-fuel partner, Highly Innovative Fuels, is now producing e-fuels at its Haru Oni plant in Chile and recently gave the go-ahead for a second plant in Texas, US.

Steve Sapsford, an independent consultant and advisor to sustainable fuel specialist Coryton, told Autocar: “The trick is using the resources for the best overall outcome. On the renewable electricity question, the key argument is that you should be making e-fuels where you have an abundance/excess of renewable energy.

“This is why the Haru Oni plant is in Chile. There is an excess of solar and wind, more than their domestic consumption, but it is difficult to export that energy as electricity to energy-hungry countries, [such as in] Europe.

“It then becomes much more attractive to use that energy to make an extremely energy-dense liquid hydrocarbon, which is easy to ship around the world.”

David Richardson, Coryton’s business development director, believes a total shift is required: “Behind the scenes, there are a lot of very worried people that are saying there’s no way that we can do this [achieve climate targets by switching solely to EVs].

“I’d rather everyone was honest and reset ourselves. Get out and ask what is now the right thing to do, instead of the short-termist – the soundbite type stuff.”